Irssi: Performance issues when closing lots of windows

Ref #582 "Set a default irssi windows limit"

Yesterday an attacker opened 1000+ private msg windows and my irssi completely froze for several minutes when I tried to close even one of these msg windows. When I tried to close many of them at once with

/window close 50 100command irssi consumed 100% of CPU and didn't seem to recover even after one hour.

New ticket to fix that problem by optimizing the commands instead of limiting windows (which is probably a good idea too)

Made some tests with variations of this:

(echo 001 a; for i in $(seq 1000); do echo ':nick'$i' PRIVMSG a :a' $RANDOM; done) | pv -Wl -L 50 | nc -l -p 6667

/script exec use Time::HiRes qw {time}; my $start = time(); Irssi::command("window close 2 1001"); print time() - $start;

Possibly not the best way to test this, but i was aiming for something somewhat close to the real thing.

Ran inside valgrind (callgrind) with instrumentation disabled (for no particular reason), performance should be half than native hardware.

All times in seconds. Data spreadsheet here

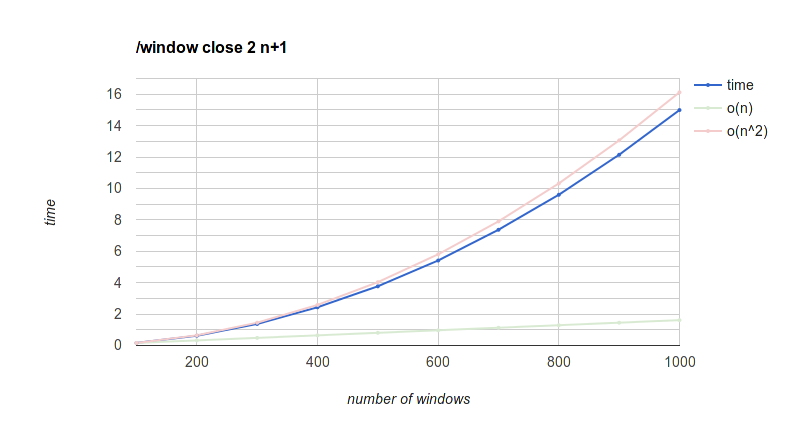

/window close with all the windows

100 to 1000 windows with steps of 100.

O(n) and O(n^2) reference lines are extrapolating from the time to close 100, where n means number of windows.

It's quadratic but the absolute times up to 1000 windows are pretty low, I think it's perfectly tolerable compared to the others. But 2000 takes a minute, 3000 takes two minutes, 4000 takes four minutes...

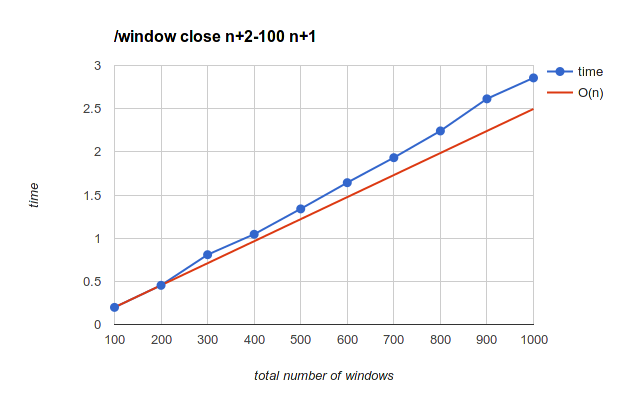

Closing the last 100 windows

100 to 1000 windows with steps of 100.

O(n) reference line is extrapolating from the difference between 100 and 200, where n means total number of windows.

This is pretty good. It takes 5 seconds to close the last 100 windows of 2000, 10 seconds on 4000 and 25 seconds on 10000, so if you're stuck with that many windows, doing this one is several times is the best way to get out of that mess (assuming we haven't fixed /window close to behave like that by default, anyway)

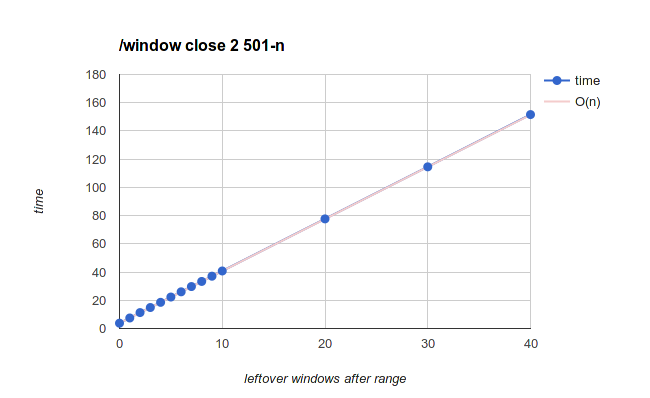

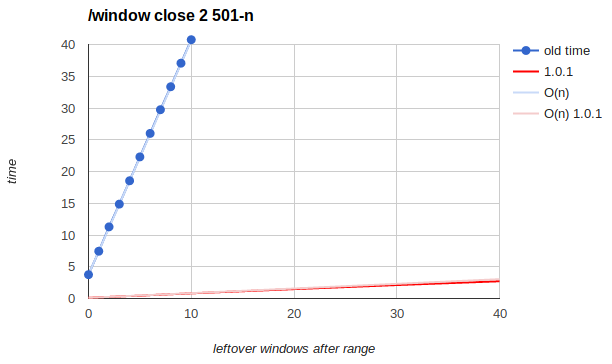

Leftover windows after range

Also known as "closing first X windows", but the windows after that hurt so much that I had to change the perspective.

Always starts from a total of 500 windows, but varying the number of windows that are not closed after the range. The number of windows that are closed decreases too but that doesn't seem to be significant

The O(n) reference line extrapolates from the difference between one leftover window and no leftover windows (3.7 seconds), where n means number of leftover windows.

It may be misleading to call this O(n) when i'm keeping the total number of windows constant, but you get the idea. Maybe call this O(n*m)?

Either way, slowest one and most likely to mess up - I've seen people doing this accidentally many times, by closing a small range of windows hoping for it to be faster than closing the whole thing. Very counter intuitive, but yeah, don't do that. Either close everything or close the last ones. Or wait until we fix this mess.

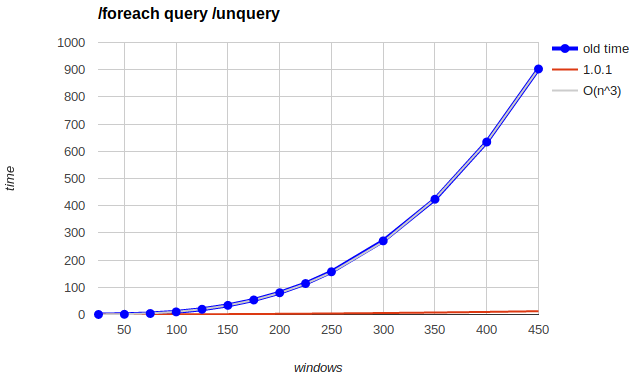

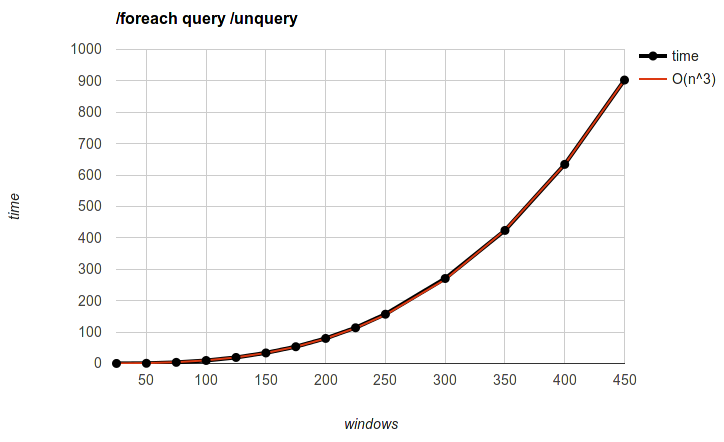

/foreach query /unquery

25 to 450 windows with steps of 25 up to 250, after which it got too slow to do the whole thing and it would be redundant anyway.

O(n^3) reference line was hand-fitted by tweaking constants until it looks close enough. @chinatsu wants me to say it is "O(0.0000098557n³ + 0.0000840573n² - 0.0089126953n - 0.2834492906)"

Second slowest, maybe? At least you can get to 100-200 without a lot of pain, unlike the leftover windows one where the intuitive way to use it (don't close all the spam at once) probably means leaving 100 leftover windows which is hardcore mode instant death

Trickier to optimize since it's general purpose. Maybe we should throw a warning like we do with /list when /foreach matches too many objects?

All 5 comments

please make some pretty pictures for #585

(I still intend to do this at some point)

I'm not sure if the performance issues are sorted out by this but at least they should be somewhat improved. may need to revisit this issue

furthermore, the window number compaction routine should be rewritten to move a block of windows at once instead of moving one at a time and renumbering all windows block-size times

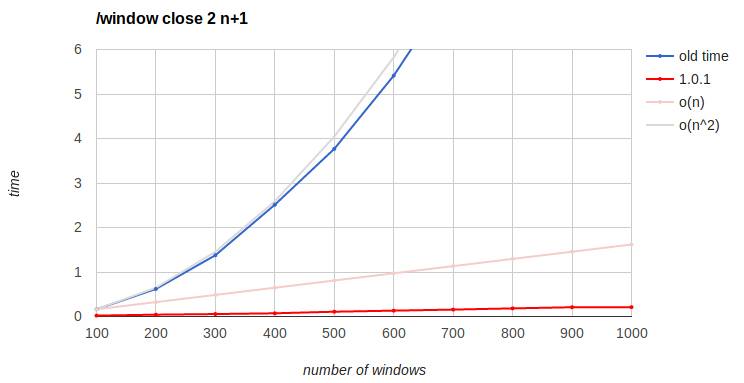

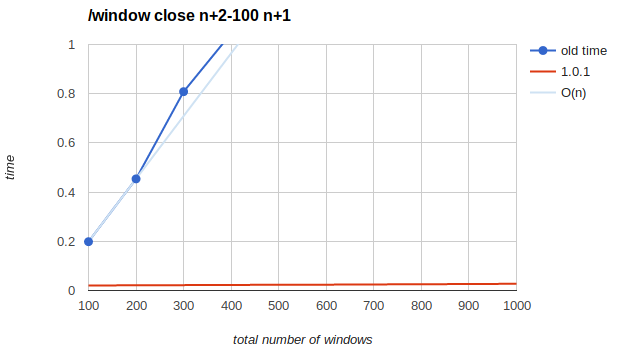

0.8.21 vs 1.0.1.

I didn't have time to do the 0.8.21 tests again, but these were run in the same environment so they are most likely comparable.

Some graphs are not really comparable, which is a great result.

/window close with all the windows

Closing the last 100 windows

Leftover windows after range

/foreach query /unquery